For those of you wanting to know more about what ONE LONG NIGHT: A Global History of Concentration Camps covers, I made a book trailer.

For those of you wanting to know more about what ONE LONG NIGHT: A Global History of Concentration Camps covers, I made a book trailer.

I first visited the site of a former concentration camp in November 2011, flying into Hamburg on the anniversary of Kristallnacht. Seventy-three years before, in 1938, a maelstrom of organized street violence directed against Jews across Germany and Austria led to the detention of tens of thousands, along with the destruction of hundreds of synagogues, thousands of businesses, and nearly a hundred deaths. At that point, I had been focusing on concentration camp history for three years. My thought was that by traveling on those dates, local commemorations for Kristallnacht in Germany might reveal how public memory had preserved or forgotten these events.

My first night in Germany was spent in Bergedorf, a suburb on the southeastern outskirts of the city. I woke up early the next morning, put my laptop into my backpack, and walked four miles to the former concentration camp at Neuengamme.

At that time, I was writing a book about the Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov and how he had folded his personal losses and his century’s tragedies into his fiction in ways that readers had missed. The aim of the trip was to find out more about Nabokov’s younger brother Sergei, who had been arrested first as a homosexual and later as a subversive, and then sent to Neuengamme.

Walking from the hotel, I wanted to see the view that those prisoners had seen, marching from Bergedorf to the former camp site as they had in the first years of the camp’s existence. Approaching the gates from the same direction on the same road, passing some of the same low-roofed houses that remain today, I hoped to glean some insight into the tiniest part of what arrival there had been like.

Neuengamme was open from December 1938 to May 1945, and more than a hundred thousand prisoners had entered its gates in that period. A reverent hush looms over the site today, but wartime pictures reveal a dense landscape of barracks, SS quarters, and administrative buildings. Sitting in the far north of Germany, it was the last major camp liberated by the Allies. On average, prisoners at Neuengamme had a life expectancy of twelve weeks. Sergei Nabokov survived 10 months there, dying in January 1945.

It took fifteen minutes to walk from one end of Neuengamme to the other. The main Nazi camps, I soon discovered, tended to be vast enterprises, not so much large camps as miniature cities of horror nestled throughout Germany—and later, in occupied territory.

Internment, detention, Soviet labor camps, and Holocaust references played such a key role in Nabokov’s work that it led me to wonder how concentration camps had even begun. I found very little on the origins of concentration camps before the Holocaust and the Gulag. I found it hard to believe that there was no English-language book about how this inhumane concept had entered the world and persisted over time.

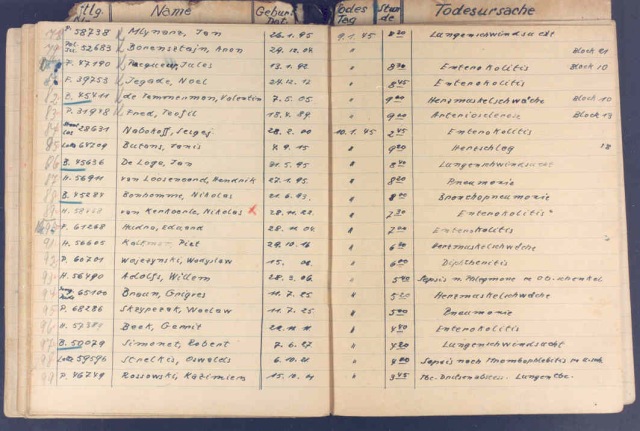

Sitting in the archives at Neuengamme concentration camp memorial in November 2011, looking at Sergei Nabokov’s name in the Totenbuch—the book of the dead—I began to think I might write that story.

During my short time at Neuengamme before heading to Berlin and Prague for other interviews and research, the memorial’s head archivist, Dr. Reimer Möller, was generous with his time. I sat down with him at one point to talk about his work and what he thought it might accomplish. It surprised me when he said that he did not do his work with any confident expectation that it would keep the same horrors from happening again. Instead, he suggested, all it was possible to do was to give people information, so they would know what had taken place. Whether that information would be enough to stop the kind of dehumanizing terror that had occurred at Neuengamme, he could not be sure.

The trip was only a week in all—far too short to do everything I had hoped to accomplish. I found the depth of commitment to detailing the history of what Nazi Germany had done extraordinary—the Neuengamme site hosts some 100,000 visitors a year. Yet as I wandered the streets of Hamburg on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, I did not see a single public reminder of or reference to the anniversary of the 1938 violence. Even when history is meticulously preserved at specific memorial locations, it sometimes remains absent from the fabric of daily life.

I returned home thinking about what is held in archives and at historic sites, and how the larger story of the camps could be shared with people who might never set foot in such a place. I decided to trace the long arc of concentration camps as a way to carry history forward, though it would be up to readers to decide whether this knowledge might make a difference.